Bottom line.

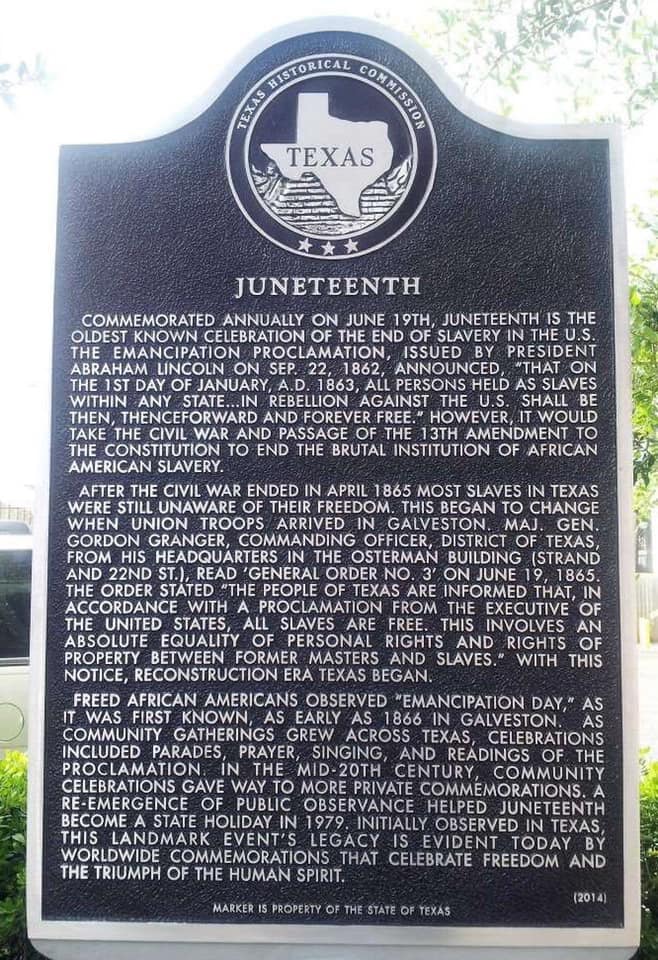

Until the Union Army arrived in Galveston with 2,000 Federal troops to occupy Texas on behalf of the Federal government Texas slave owners did not recognize the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862.

—-

During the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, with an effective date of January 1, 1863. It declared that all enslaved persons in the Confederate States of America in rebellion and not in Union hands were to be freed. This excluded the five states known later as border states, which were the four “slave states” not in rebellion – Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, and Missouri – and those counties of Virginia soon to form the state of West Virginia, and also the three zones under Union occupation: the state of Tennessee, lower Louisiana, and Southeast Virginia.

More isolated geographically, Texas was not a battleground, and thus the people held there as slaves were not affected by the Emancipation Proclamation unless they escaped. Planters and other slaveholders had migrated into Texas from eastern states to escape the fighting, and many brought enslaved people with them, increasing by the thousands the enslaved population in the state at the end of the Civil War. Although most enslaved people lived in rural areas, more than 1,000 resided in both Galveston and Houston by 1860, with several hundred in other large towns. By 1865, there were an estimated 250,000 enslaved people in Texas.

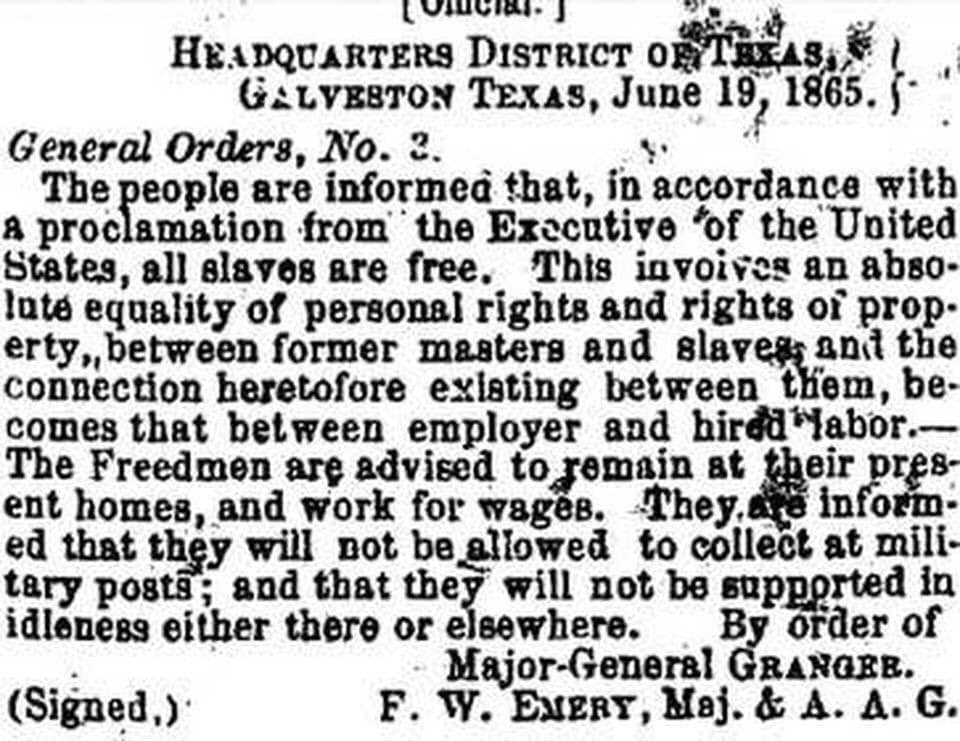

The news of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9 reached Texas later in the month. The Army of the Trans-Mississippi did not surrender until June 2. On June 18, Union Army General Gordon Granger arrived at Galveston Island with 2,000 federal troops to occupy Texas on behalf of the federal government. The following day, standing on the balcony of Galveston’s Ashton Villa, Granger read aloud the contents of “General Order No. 3”, announcing the total emancipation of those held as slaves:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.